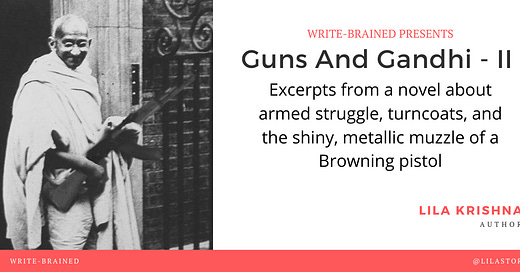

Guns And Gandhi II - Moar Guns, Moar Gandhi

Warning: Contains 19th century women salivating over the sweet, shiny muzzle of a Browning

I’m at an impasse with this novel, one that I hope to snap out of in a couple of weeks. I’m just not sure how my novel comes across, and I’m having difficulty grasping the core of it. I have beta readers working on giving me their impressions, and I, too, am going back to my sources to get a sense of the emotional landscape of living in 1906 London, and of hanging out at India House.

The last couple of bits I wrote, I hold very close to my heart. Both are follow-ups to the pieces I posted last week.

In the first excerpt I’m going to share here, I’m following up to what happened after Tatya sent the guns to India. Someone had to receive it, right? I originally wanted to show those pistols being used, but that didn’t happen until much later in the sequence of events. So instead, I’m writing about how it was received. I thought about a commonplace door-to-door saree salesman showing up on a dusty, narrow street in Nasik, and the rest of the scene just wrote itself.

My second scene is a follow up to the gang speculating on Gandhi’s arrival in India house. Gandhi arrives. And everyone is annoyed by him as expected. A lot of it could just be projection, but it’s grounded in some observations of eyewitnesses to that scene, and of people who met Gandhi back in the day. The more I piece together about Gandhi, the more he seems like an image-conscious person who always tried to be on the winning side, and tried really hard to project himself as one of the people, when it was pretty obvious he came from a place of privilege, ignorance, and insensitivity.

Here’s the first excerpt. I simply loved delving into a very feminine setting, after the sausage-fest that has been the book so far.

“Sarees! Sarees!” A turbaned man screamed as he walked down the narrow streets of Nashik. “Colorful sarees! Beautiful sarees! Paithani! Kolhapuri! Ilkal, Banarasi!” He screamed.

“Ma! The saree man is here!” shrieked a young boy by the gate.

“Go bring him here!” His mother said, as his aunt stood by, infant on her hip.

“Paithani! Kolhapuri! Ilkal! Banarasi!” The man screamed. Women were starting to step out of their gates.

“Kaka, my mother and aunt want sarees!” said the boy, running to the man.

The man followed the boy straight to their home, as the other women fumed.

As he spread out his wares from the many packages he carried on his head, he pulled out a simply wrapped brown package.

“This is for you, sister,” he said, handing it to the boy’s mother. The aunt quickly let down her infant and took away the package.

“Kaki! What is that?” screamed the boy, “Can I see?”

“Later, first bring saree-kaka a glass of water, like a good boy.” His mother said.

“Thank you so much,” the boy’s mother said, “Our Tatya hasn’t seen us, or even his baby in a year,” she indicated the toddler, who was now pulling at a saree on the floor. His mother quickly swept him up in her arms. “This is the only way he can send him toys.”

They talked and tried on as the turbaned man unraveled saree after saree, discussing its merits, and upselling the grand bananasi silks.

“We’ll take the blue ilkal and the red gadwal” the boy’s mother said finally.

“What, no silks?” The saree man said, mock-shocked, “Grand women like you must have grand sarees! Madam for instance is tall and fair, she would look delightful in this broadly-bordered Kolhapuri silk,” he said, indicating the boy’s aunt, “It is simply made for you, madam.”

It took some effort to ward off the saree salesman’s expert upselling, but not before they took an extra gadwal as a compromise. The man left with a huge tip, and into a crowd of waiting women outside.

The boy’s aunt ran to the store room in the inner recess of the house. The boy’s mother followed.

She ripped open the plain brown packaging, and ten fat books for children fell out.

She rummaged among them until she came to the one by E Nesbit, and opened it. “Exquisite isn’t it?” She said.

“Beautiful,” said the boy’s aunt, running her fingers on the smooth, shiny metal surface of the Browning pistol embedded in the book.

“Tch, don’t touch!” the boy’s mother said, and playfully slapped her co-sister’s hands off the pistol. She then carefully rubbed over the pistol with the soft end of her cottons saree.

“I want to learn to shoot one.” The boy’s aunt said.

“Amma!” said the infant from the door of the store room, and the women snapped the book shut, and put it away in a vat of grain.

“One of these days,” said the boy’s mother, laughing.

And here is Gandhi’s first appearance in India House, way before the events in the movie, Gandhi. If India House gets made into a Netflix/Prime/Zee 5 series, this would be the youngest-ever that Gandhi was portrayed on screen. Wouldn’t that be grand?

The comments Gandhi makes about native South Africans is not something I conjured in my mind; he did in fact say those things, as is attested in several books and historical records.

It is easy to dismiss his racism as “a man of his times”, but the fact is, there were several men in his own times, and from the same background as him, who knew better and saw all men as equal. That is what I seek to portray here. There were a houseful of his contemporaries who considered his attitude utterly shameful.

A small, smart, spry man walked in the door. He had on a smartly tailored suit, but the material didn’t hang quite right. He immediately went for Shyamji, and fell at his feet. We all watched, amused. The word ‘oily’ was quite right.

A large, dark man followed, and skulked in the background.

“I’m Mohan,” the small man said, introducing himself, “I’ve heard a lot about all of you from Panditji.”

“As have we,” Hardayal said, “How has your journey been? You must be tired.”

“Not bad, not bad, we freshened up in the hotel, so we are quite well rested.”

We all introduced ourselves to Mohandas Gandhi. The tall, dark man continued to skulk.

“Hello sir,” I said, addressing the tall dark man, “I’m Herjoat Khosla. And yourself?”

The man opened his mouth to speak, like he was not used to being addressed at all.

“Govender,” he said, “I work with Mr. Gandhi.”

“Both of you, please sit, make yourselves comfortable.” Hardayal said, indicating the many chairs around the dining table. “Would you like some chai? Snacks? Tatya is making some right now.”

“Tatyarao?” Mohan said, “the Puneri? I have heard of him from Bal-bhau.”

“The very same.” Hardayal said.

Mohan sat down and patted his silk kerchief over his lined brow and greying temples. He was much older than most of us. His ears stuck out a lot. His was probably not one of those communities where they considered elephant ears a sign of stupidity.

Madanlal brought a tray of chai and offered it to everyone. “It’s the new box from Darjeeling!” He said excitedly.

“Ah, chai, it is difficult to get the good stuff in Natal.” Mohan sipped his tea excitedly.

“Snacks ready!” Tatya called.

He brought out a kadai full of fragrant kolambi masala, and served each of us around the table. My nostrils filled with the smell of coconut, spices, and prawn. It was hard to believe Tatya had only recently learned how to cook meat and seafood.

“Now I had to make do with dry coconut, not fresh ones, and no one is more upset about that than I, so don’t any of you dare complain.” He said.

“It’s very good, sir.” Govender said, eating heartily, “If you add hot water to the dry coconut, it almost tastes fresh”.

“What is this?” Mohan asked, not touching his plate.

“Kolambi masala. Prawn curry.”

“Jhinga.” Shyamji added helpfully in Gujarati.

“My apologies, I will not partake,” Mohan said, and pushed his plate away.

Tatya had labored over the mix of spices all morning, and unlike women like my sister-in-law, who were used to hosting luncheons and catering to varied palates, was not used to tantrums about food.

Heck, I had never seen him complain about food, or refuse to eat, or even throw away badly-cooked food. Years of poverty has that effect on one. Mohandas Gandhi must have seemed to him like a spoiled brat used to demanding this, that and everything, and getting his way.

The surprise made him react with belligerence.

“If you don’t eat with us, how will you work with us?” Tatya asked with a smile.

“Aren’t you a Chitpavan Brahmin?” Mohan continued, “How come you are cooking prawns, and so well at that?” The compliment and kind tone didn’t quite hide the disgust and consternation in his face.

Tatya went pale, and his smile vanished. Hardayal braced himself for the fight that was to erupt. Everyone else’s jaws dropped at Mohan’s comment.

Being so far away from home, and being so few in number, it made no sense to focus on caste, religion, region, language, or any of the other innumerable divisions that kept people apart in India. Most of us might adhere to the rules and rituals we had grown up with privately, but calling out someone for their caste seemed like tacky, narrow-minded, low behavior. Had this man really lived in London for several years? How did he manage in South Africa, where you got a thousand varieties of bushmeat and offal and biltong? Did he never step outside his bubble of Gujaratis? Dr. Rajan and Pandit Shyamji staunchly remained vegetarian, but I had never heard them, or any of the vegetarians I knew, consider it a superior diet. Tatya himself, a lifelong vegetarian, had taken easily to meat, and would vociferously shut down any discussion where people brought up their caste. “And your blood is green, I suppose.” He would say.

After a momentary flash of anger, Tatya was back to his old, composed, belligerent self.

“Mohanji,” he said, “this is just fried prawn. There are lots of us who want to fry and eat the British alive. Are you sure you have the stomach for that?”

“Violence is never the answer.” Mohan said simply.

Harnam, attempting to diffuse the situation, said “Your idea is one of passive resistance, isn’t it, Mohanji? I’ve read an article you had written.”

“Yes, we used it to great effect to enact policies in South Africa.”

“Remind me, was that for the separate entrances between the Blacks and Indians at the post office in Durban or something?” Dr. Rajan said, slyly looking at Tatya, who was now happily tucking into the prawns, with a generous topping of coconut.

“Yes, that was quite a struggle to get us Indians classed separately.” Mohan said, his air of self-righteousness returning, “They thought we were the same as those damn kaffirs!” He shuddered, “We are not animals! It’s not our lot to spend our life in indolence and nakedness. Why should we be classified with people who do?”

“Mr. Gandhi,” I said, unable to take even a single second more of this, “Please keep this in mind. How you look at the African man, that is how the white man looks at you.”

“That is exactly what we fought against. And won.”

“There are plenty of our own countrymen who you can say spend their whole life in ‘indolence’ and ‘nakedness’. Are they not worthy of equality and respect, in your eyes?” Tatya asked.

“We have a long way to go in our own country, and need to educate a large part of the population on good and bad behaviors. I think everyone is capable of learning and change, even the Chandals,” Mohan said, using that derogatory word. Tatya’s eyes flashed. “Isn’t this what is all of our ultimate aim here?”

Exhausted, I looked toward Shyamji. Everyone else at the table was doing the same.

“There is a long way towards home rule and complete independence,” Shyamji said, “And all of us have a part to play, I’m sure. Isn’t that what you are here for, Mohanji?”

“Yes, yes,” Mohan said, relieved to have to talk about himself again, and launched into a long spiel on all his reasons for traveling to London. We, too, kept the conversation focused on him for the rest of the afternoon, we simply didn’t know where to start with unpacking all his twisted, confused ideas.

At the end of the long afternoon, Mohan collected all our drunk tea glasses and snack plates, and washed them in the sink himself, despite our protests.

“We were going to wash it ourselves anyway?” I muttered to Tatya.

“Don’t you know, our currency is now empty gestures? Get with the times, Herjoat!” He whispered back.

We giggled. Shyamji shot us a disapproving look. We bit our tongues long enough to bid Mohan a polite farewell. The moment his motor-car disappeared to the end of the street, a roar erupted in the house.

We would talk about nothing else for days.