Guns And Gandhi - Excerpts from India House

All characters and events in this excerpt are completely fictional, and any resemblance to people dead or alive is entirely coincidental.

I haven’t been sending out my Thursday emails for a couple of reasons. One, trying to maintain productivity in these trying times has been challenging, and Thursday emails were what I lavished a lot of time and attention on, and I can’t as much anymore. Secondly, I’ve become much more susceptible to throat issues, and this is the wrong time to aggravate them, which is why I would prefer to not record podcasts.

That thankfully leads to some extra time available for me to make progress on India House. Doing my research, I’ve realized this can be a series with several parts, though it remains to be seen how I deliver on them. Every series needs a name, and I have come up with The Krantikari Chronicles.

So my novel is now India House (Book 1 in The Krantikari Chronicles). Ideas for sequels include Book 2 - Ghadar, Book 3 - The Pan-Asian Conspiracy, Book 4 - The Indian National Army, Book 5 - Red Fort Trials, and if it makes sense at that point, Book 6 - Gumnaami Baba, which might revisit everyone from the previous books. But this is just a blueprint, and it looks like daunting work. I hope I at least publish the first one.

Anyway. On to the excerpts.

I’ve made decent progress with India House, with the manuscript at 23,000 words. I had a lot of fun writing two particular scenes. The first involves Guns, and the second involves Gandhi.

The first one is this episode of gun-running. Guns were difficult to get in India in the 1900s unless you were a ‘martial race’ who were considered friendly to the British. So the revolutionaries in London tried to send guns to their compatriots in India, and they did so in ingenious ways.

Here’s an attempt at imagining what that might have looked like. For context, the narrator is Herjoat, a young man who runs his family’s textile business, and the location is India House in Highgate, London.

Gun Running

Sure enough, they put up a gun range. I had been away in Italy for a couple of weeks, ensuring some shipments went through. When I returned, a discreet corner of the back lawn had been made into a shooting range.

They had put up a shamiyana, a closed tent like you would at an Indian gathering, and had padded up the cloth walls with thicker, more heavily padded cloth and wood to muffle the sound of the shots.

Tatya was practicing shooting under the tutelage of Bapat.

“Grip it hard with all your fingers, it’s okay. You don’t need any finger other than your trigger finger.” Bapat was saying.

Tatya was standing firm, his legs a little apart. His eyes were focused on the target, which had on it the Union Jack. There were a few bullet holes here and there, but none were close to the center.

“Hold the gun up! It should be aligned straight with your hand! Otherwise, it won’t hit the target!”

Tatya corrected his alignment.

“Like I told you the last time, you need to put your head back. You fell back from the recoil, remember. Throw your head back a little.”

Tatya threw his head back.

“Not that much!” Bapat corrected his posture.

“Okay, ready, shoot!”

The gunshot rang out, and grazed the bottom of the target.

“I told you! You need to align your gun!” Bapat said, “Oh hey, Herjoat, welcome to our new gun range. Want to have a go?”

I thought about my fingerprints on a strange gun that Bapat, with his ideas about justified murder, had access to.

“I’ll watch. It’s fun watching Tatya fail.” I said.

“Never make fun of a man with a gun in his hand, Herjoat.” Bapat said.

“Bapat-bhau! Don’t scare the boy! Herjoat, these are blanks. Not real bullets.” Tatya said, “Okay, I’m going again. I think this posture doesn’t work for me like it works for you. Dr. Rajan’s method works better.”

Tatya stood firm, holding the gun slightly to his left with both hands. His left hand bent a little, while his right was fully stretched out.

“Easier to align the gun to my arms like this,” He said.

“Perfect stance. Aim and shoot.” Bapat said.

The shot rang through, and hit the Union Jack only a little above the center.

“Much better. Keep practicing.” Bapat said.

Hardayal entered the tent.

“Having fun, I see. May I try?”

“Here he’s come to show us all up.” Tatya said, handing his gun to Hardayal, “Keep doing them bulls-eyes like you did all day yesterday. It needs more bullets.” Tatya indicated a cupboard, from which Hardayal retrieved a box of shot.

“Where do you people get these guns from?” I asked. I was curious. How was it so easy for them to get handguns, when learning to shoot was such a difficult project?

“Rifles are everywhere. You don’t need permissions to buy them. You just walk into a store and get a few, along with some shot.” Bapat said. “Handguns are trickier. You need a license to buy from a gun store. You can get one at the Post Office, but why risk that. Instead, you can buy them from private citizens who want to get rid of theirs.”

“Oh! Why would anyone want to get rid of their gun?”

Tatya shrugged. “We got this one from an old lady at a church sale. She was disposing off of her dead husband’s possessions. We got a few more from rummage sales, estate sales.”

“There’s also ads in the classifieds columns of the newspapers. Just need to keep an eye out for them”

“Ingenious,” I said. “At this rate we’ll have our own small army.”

They laughed.

“I’m going inside for a snack.” Tatya announced, “Herjoat, you must be hungry.”

I went into the house with Tatya, and he led me up to his room.

“I have a request for you,” He said.

“What is it?”

“I have some possessions I’d like carefully sent home,” Tatya said.

“I can try helping with that,” I said, “But I can’t promise anything.”

“I understand.”

“Can I see what you want to send home?”

Tatya brought out two unbelievably thick children’s books. One was ‘The World Of Peter Rabbit’ by Beatrix Potter, and the other was a nicely bound hardcover edition of _The Story Of The Treasure Seekers_ by E Nesbit. I knew Beatrix Potter, my niece loved those books.

“Nice, for your son?”

Tatya smiled, his eyes misting over a little. “Open it,” he said, handing me the books.

They felt heavy. I opened the Beatrix Potter book. The hardcover just flipped open. The pages had been glued together, and a hollow cut out in them.

Inside was a Browning pistol.

I gasped involuntarily.

I quickly opened the E. Nesbit book, and it, too, had in it a Browning pistol.

“You want me to send this to your family.” I said.

“It would be nice to. The next time you’re travelling to Bombay, I’ll ask my brother to receive you at the dock. My sister-in-law is a wonderful cook. They would love you to stay with them for a few days.”

“I cannot do that.”

“I understand.” Tatya sighed.

I thought a little. It would definitely be suicide to be seen with Tatya’s family. Even if I was not being tailed, Tatya’s entire family surely was. And handing off material in Bombay was incredibly dangerous. The police there had too much authority.

But my business sent and received packages, small and large, all over the country, every day.

“Do you know of any cloth mill, or door-to-door garment salesman near your home?”

“Yes!”

“Have them place an order with our company. I’ll take care of the rest.”

Tatya hugged me hard. I didn’t expect such a frail man to have such a strong hug, but he knocked the breath out of my lungs.

He proceeded to thank me profusely.

“This never happened,” I said, putting the books into my briefcase, and walked to the dining room.

Here’s a second excerpt which I had a lot of fun writing. I haven’t written the follow up to this scene yet, and I am really looking forward to it, and after you read this, I’m sure you will too.

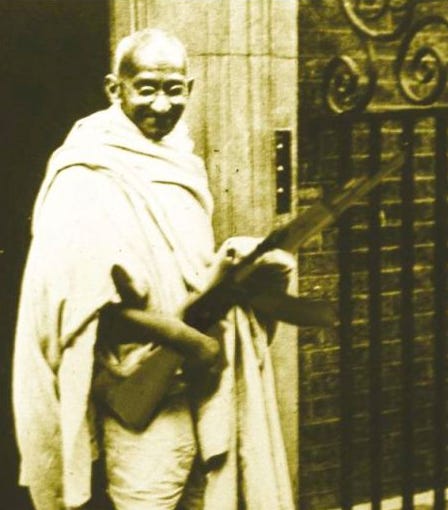

In 1906, Gandhi stayed over at India House for a couple of days. From their writings, I know the residents, and Shyamji Krishna Varma, the owner of the house, didn’t particularly like Gandhi. Also this was at least ten years before he returned to India and joined the Indian National Congress, so he was much less known than most of these people.

Let’s see how these votaries of armed revolution anticipated the arrival of Gandhi.

Waiting for Mohandas

I hadn’t seen Tatya in a couple of months. He had started on his programme at Gray’s Inn, which took up his afternoons and evenings, and when it didn’t, he was busy at the library or in his room, writing his book. I had taken up with Betty, whose father ran the pub down my street. Obviously my brother couldn’t know, and I spent all my mornings and afternoons at her flat, when I wasn’t buried in work.

I strolled over to India House one Saturday, when Betty was away visiting relatives in Yorkshire. Everyone was in the dining hall, and seemed worked up.

“Do we have to be welcoming?” Tatya said sourly.

“Be nice to him, he might end up powerful.” Shyamji said.

“Him? How?”

“Don’t you see him cosying up to the British in South Africa? He fought for the right of Indians to side with the British against the Boers. And most recently, he strongly supported the British putting down the Zulu nation.” Shyamji said.

“Rat bastard.” Hardayal muttered.

“How can someone claim to be for non-violence and compassion and then agree to wanton violence on native people by colonial powers in their own land?” Harnam said.

Dr. Rajan just sat there, shaking his head.

“He was completely fine with the partition of Bengal.” Abdul said, shaking his head in disappointment, “I don’t want to be polite to him.”

“He keeps annoying Tilak-bhau with requests to adopt the path of non-violence. Tilak-bhau doesn’t want to entertain him, and he won’t stop. He just wants an in with the Congress, it strikes me.” Tatya said.

“Who are we talking about?” I piped up.

“Mohandas Gandhi, of course,” Tatya said, “Who else has such a long list of sins to his name?”

The name sounded familiar. “Who is he?”

“Yet another Gujarati barrister in South Africa. Was right here at the Inner Temple 15 years ago, couldn’t succeed here, wanted to leave. And then some Gujaratis called him to Natal. Oily fellow. Holier-than-thou, but smooth-talking. People listen to him. So I suggest we pretend to as well.” Shyamji said.

“He annoys all of us just in his articles. I shudder to think how it’s going to be with him here.” Hardayal said.

“Why did you invite him here, Panditji?” Tatya whined.

“You people have to learn. He is the sort you will have to fight, like how Balji, Bipinda and I have to take nonsense from the Congress. You’re all too spoiled from fighting just the British. They are an easy target. Learn how to also fight your own countrymen when they favour the British. It’s an important skill.” Shyamji grinned.

“Can’t we just implicate him in something and then he’ll get deported?” Madanlal complained.

Shyamji shook his head and chuckled.

“You boys really have to pull up your socks. Gandhi isn’t yet in the Congress, but he is going to be. That’s inevitable. The British will certainly want it that way. Don’t you want to have your own stories of when you met him, to tell your grandchildren?”

“Stop scaring the boys, Panditji.” Dr. Rajan laughed.

Shyamji shrugged and grinned broadly.

“It’s just a couple of days. You’ll learn something new from someone different. It’ll build character.”

“When is he expected?” Hardayal said, getting up and stretching.

“Around now.”

I sat back in my chair. I wanted to meet this Mohan Gandhi. He seemed like an interesting sociopath.