The Emergency, Goebbels of India, and Bollywood

Notes on Vidya Charan Shukla from Janardhan Thakur

Janardhan Thakur’s All The Prime Minister’s Men is a treasure trove of information about the Congress of the 1960s and 1970s. I found this chapter quite interesting about the Minister of Propaganda (official title, Minister for State under the Information & Broadcasting ministry) during the Emergency.

Vidya Charan Shukla was from Raipur, and his father was the first Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh. He was an MP for several terms from Mahasamund and Raipur. He was killed in 2013 in a Naxal attack in Chattisgarh.

Thakur starts the chapter thus,

To compare Vidya Charan Shukla to Joseph Goebbels is to insult the great Nazi manipulator of minds. For Dr. Goebbels was an astonishingly gifted propagandist of modern times, the real creator of the Fuhrer cult. Goebbels had brains, and that was the difference. Having no mind, Shukla brought with him police batons to beat minds out of existence and succeeded in totally destroying the credibility of the government and his masters. {..} But let it pass, it would do no harm to call him a Goebbels; nobody would mind an insult to Hitler’s drum-beater.

Further, he says

The stories of his misdoings were too well-known even then. Indira Gandhi had heard of Shukla’s “extra-curricular” activities, but they did not make any difference to her. And soon people in the party and the government came to believe that the more unsavoury a man’s private life, the better his chances of continuing in grace

We can take for granted that this bad behavior comes from spoiled sons of men in power who never get told no and have a busy father and a clueless mother at home. And this was also an Indira Gandhi era thing, I suppose. Not necessarily because of her personally, but that was also the time when the children of the first crop of post-independence leaders were grown up.

This next bit is during the declaration of Emergency. The Emergency was a period from 1975 to 1977 when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi cited internal and external threats to India and suspended civil liberties. It is quite illustrative of the Emergency

On 29 June 1975, Shukla called the foreign journalists to Shastri Bhawan and told them that any correspondent not complying with censorship regulations would be subjected to “very stern and stiff action” which could mean expulsion. “This is not a threat o a warning. Just a statement of fact in plain language”.

Sitting in the front row was Lewis Simons, the young, bearded correspondent of the Washington Post. He was taking down every word in his notebook.

Shukla looked at him hard and asked, “Why are you writing this donw?”

“Because you’re saying it!” replied Simons.

“No, no, this is not for reporting,” the minister said. Simons went on writing

Over 50 foreign journalists sat in the hall, watching the arrogant performance of the Indian version of Goebbels.

“You will be judged not only on the basis of your despatches,” Shukla said, “but also on the basis of what your newspapers write, and on our Home Ministry files on you”

{…} The very next day, Lewis Simons got a long-distance call from his Editor in Washington. “You better expect to be expelled from the country,” the editor told him.

The Indian embassy in Washington had got in touch with the Washington Post editor and told him to recall Simons from India or else he might have to be deported. The editor had replied that he saw no reason why he should recall his correspondent.

What had enranged the Indian government against Simons was his report on the 18th June Rally of Indira Gandhi at New Delhi Boat Club. Quoting ‘military sources’, Simons had written that the defence minister Swaran Singh had requested the Army to deploy soldiers in civilian dress for security purposes at the rally, and that the Army had turned down the request saying that if the soldiers were to be deployed, they had to be in their uniforms.

This bit of information, that Simons thought was interesting, was tucked away somewhere in the midst of his long despatch. If he had known that the Indira Gandhi government would zero in on that bit of fact, perhaps he wouldn’t have used it, or perhaps he might have led the story with it, since it was all that important. But in any case, he had written that story when India was still a free country; he had never imagined that the situation would get far worse here than even in Nazi Germany.

I’m not sure it was “worse than Nazi Germany” as Mr. Thakur puts it. But it was quite a bleak time.

This journalist gets forced to leave the country on threat of arrest and his notebooks get confiscated at the security check.

Another journalist’s account of censorship as he waited for the censor officer to approve of his despatch:

The censor looked up at them and took their reports. Soon he was crossing out line after line. The correspondent protested, “Why have you crossed out the sentence dealing with the suspension of the fundamental rights? That’s part of the official ordinance!”

The censor looked up and said, “Because fundamental rights have not been suspended for the average person. It applies only to people who have been detained. They have no right to appeal to courts.

“But that means fundamental rights have been suspended!” the frustrated correspondent pleaded.

“You are wrong” the censor replied as he continued to strike out more sentences.

“But why have you cut out the lines suggesting that the demonstrations against Mrs. Gandhi have fizzled out?” the correspondent asked, his voice rising to a higher pitch.

“Because nobody would want to plan a demonstration against the Prime Minister in the first place. And, by the way, you cannot pass this message informing your editor that this report has been censored.”

“But it has been censored,” the correspondent remonstrated.

“That does not matter, you cannot say it.”

There are several pages dedicated to Vidya Charan Shukla’s shenanigans in Bollywood. I’ll restrict it to names I recognize.

The moment Shukla stepped into Shastri Bhawan, he set his sights on Bombay, the filmland. That was to be his real playground in the next 19 months. Driving from the Santa Cruz airport into Bombay city one day, Shukla’s eyes got stuck on a huge wayside hoarding spilling over with inviting flesh. Must have caused a flutter in his heart, but at a meeting with film producers later that evening, he assumed the posture of a great purist.

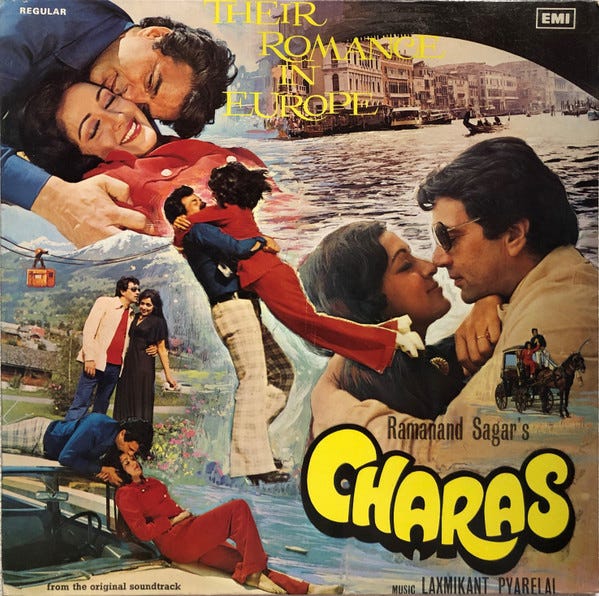

“Who is this Ramanand Sagar?” he haughtily demanded.

Sagar raised his hand meekly and rose from his seat.

“I have seen hoardings of Charas on my way from the airport,” barked Shukla, “How dare you advertise the film before it is censored? Such films are alien to our culture. I’ll see to it that it is not passed”. Sagar had gone ashen. Was this the end of his Rs. 80-lakh star-studded extravaganza?

The very next day, the film was passed by the censor. A film correspondent wrote “What transpired during that kali raat (dark night) is not known. What priceless treasures were offered by Ramanand to get his {movie} passed is also not known. Only the four walls of Shukha’s hotel suite were the mute witnesses…”

But he did have his favorites:

This great crusader against sex and violence in film turned most permissive when it came to Sholay, which became the epitome of filmy sex and violence. Cowardly as all bullies are, Shukla never even mentioned the name of this film, because it featured a close friend of Sanjay Gandhi.

Amitabh Bachchan, often called “the Sanjay of Filmland” was not only a friend of the Prince, but the son of Teji Bachchan, a favourite of Jawaharlal Nehru and a friend of Indira Gandhi.

And actresses were not spared

Shukla was allegedly smitten by an actress called Vidya Sinha. She was a member of the Indian team led by Shukla to the Canadian film festival. According to one film journal, the minister knocked at the door of her hotel room and said “My name is Vidya, your name is Vidya…”

Another journal said “Unconfirmed reports which demand a probe allege that Vidya was in tears because of the knock-knock on her door at nights. Once she had to take shelter with the Chopras (producer BR chopra and his wife) and Shukla kept telling Vidya “We have a common name!’ Back in India, the actress is reported to have said “Never again will I attend a film festival in the company of this man!”

But that wasn’t a universal experience.

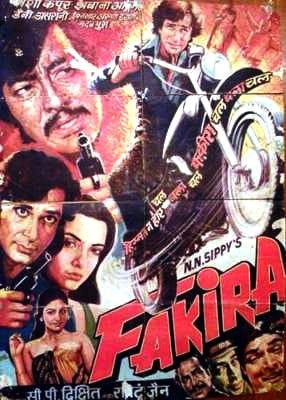

Shabana Azmi, who accompanied Shukla to the Tashkent Film Festival is quoted as having said of him, “Oh, he’s so handsome. He’s a killer” (a pre-poll statement). The minister is said to have declared that her film Fakira would not be cleared by the censor, and yet soon after their return from Tashkent, the film was passed with just minor cuts

It should be noted here that Shabana Azmi, as well as her parents, were card-carrying members of the Communist Party, which was the only political party supporting Indira Gandhi’s actions.

And Katy Mirza, who had been a Playboy bunny, attempted Bollywood, and this is what happened to her:

“He (Shukla) complimented me on my figure and took down my room number. During the night, he rang up after every ten minutes saying “Please come to my room, Katy.” Of course, I did not go”.

Janardhan Thakur concludes this section:

There are numerous stories of this kind, but enough is enough. How long can you go on with stuff like this? Wouldn’t you rather believe Shukla when he says it was his lifestyle which created this “false image” of him? He claims he has a “happy married life” and no outsider can question that. Nor that he has three charming daughters.

When I read Tavleen Singh’s Durbar, I got the impression that every present day problem in India has its origin in the era when Rajiv Gandhi and his friends came into the picture after Sanjay Gandhi’s demise. But these issues like corruption, abuse of power, and abuse of women by politicians seem to have been set in the landscape in the Sanjay Gandhi era.

Literally every negative politician stereotype seems to have come from the Indira Gandhi era, and those of us born in the ‘80s or later have no idea. We just assume that’s how politicians in India are. But the standards seem to have been set by one family, and we would do well to remember that.