The Beautiful Tree #5 - How Indian Education Was Funded in the 18th Century

And how it was defunded in the 19th century

We’ve been reading the book The Beautiful Tree - Indian Indigenous Education In The 18th Century for the past five weeks. In the first article, we went into what British education was like in the 18th century. In the second, we explored how the Scottish Highland clearances led to the Scottish enlightenment, which then led to the field of Indology. In the third and fourth articles, we got into the meat of it all - what was Indian education like in the 18th century?

We found that there was a ‘school in every village’, with some administrators estimating 100,000 schools in Bengal and Bihar. Education was free for everyone, and schools represented the diversity of the community around them. Girls seem to have been educated at home. There were plenty of institutes of higher education as well, which had many different ways of subsidizing students.

Today, we’ll explore how these schools were funded, and why the coming of the British depleted these sources of funding.

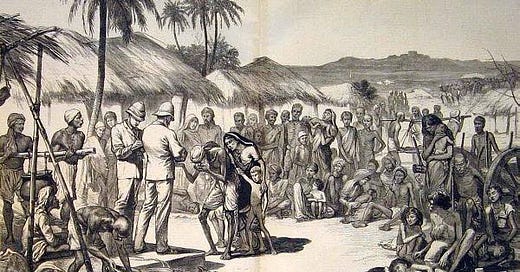

The British Caused The Decline of Indian education

It is normal to wonder if the cause of the decline was the general atmosphere of war and anarchy in the late 18th and early 19th century rather than anything specifically attributable to the British.

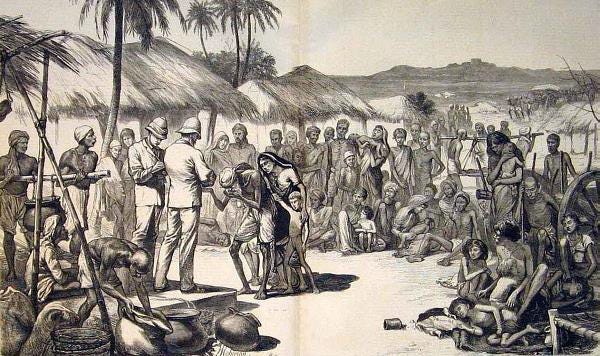

The impression from the Madras presidency survey, the Adams report on Bengal and Bihar, as well as the Punjab survey, is a sense of widespread neglect and decline in the education system. Descriptions of life and society provided by accounts of Europeans in the 18th century about different parts of India, present a relatively lively and prosperous society and data on exports from India back it up. The subsequent decades have accounts of misery and decay, and it is hard not to say they originated with European rule. In the 1769-1770 famine in Bengal, more than a third of the population perished. This would keep occurring wherever British rule took over. Imagine how many skilled people including teachers, merchants, craftsmen, soldiers, all were emaciated at best and dead at worst this way.

Dharampal presents numbers of students enrolled in education, and we can see the decline.

The collectors and surveyors of Bengal, Bihar and Madras themselves indicate that they notice a decline and a ‘great decay’ in the state of education compared to before. The population of Madras Presidency in 1823 was 12 million, and the 1822-25 survey put those in ordinary schools at over 150,000. Given them noticing a decay already, we can assume the school enrollment numbers were much higher 20-30 years earlier. The calculations assume a ninth of the population were of schoolgoing age, and half were girls, so that would be 600,000. The number enrolled in school was estimated by surveyors then as being 25% of the children, which checks out with these numbers.

A half a century later, there was another report in 1879-90. The number of students in school was approximately 270,000, with 240,000 boys and about 30,000 girls. The total population of the presidency by now was 31 million. There were more girls attending these schools than before, but the proportion of boys attending came down. Using the same calculation as before, the number of boys of schoolgoing age would be 1.7 million. When you see what proportion of boys were enrolled in school, it comes to 12.58%! Even if you add the numbers of students in every type of education, the proportion only goes up to 13.74%!

In 1884-85, the number of male scholars only came up to 22.15%, and those in school were at 18.33%, still much lower than the 1822-1825 official proportions. Also while overall number of girls in schools had gone up, the number of Muslim girls in Malabar schools was 705. In 1823, the numbers had been 1122, and the population of the district was half of the 1884-85 numbers.

In 1895-96, the number of males in educational institutions went up to 34.4%, just about equal to the proportion which had been calculated in 1826. But the number of boys in schools was just 28%. By 1900, this number was at 27.8%.

Now mind, the people calculating all these numbers were British officials. They had every reason to want to show their system in the best light and the previous system in a dim light. And yet, even in the most sympathetic light, the numbers barely get to the old decayed numbers.

How Education in India was funded (and how the funding was taken away by the British)

Prior to the British, there were three types of lands for revenue purposes, in Bengal and Bihar, and no doubt there were similar arrangements in other parts of the country. The three were:

Khalsa: Land whose revenue went to the ruler’s treasury. This was less than 20% of the land.

Chakeran Zemin: Revenue from this land was allocated to individuals involved in administrative, economic, and accounting functions, who were compensated through these assignments.

Bazee Zemin: Revenue from this land directed toward religious and charitable allowances, which supported temples, mosques, dargahs, mathas, chatrams, and grants to scholars, poets, medical practitioners, and even jesters.

Now I understand when a King would give an official “eighteen villages”. The taxes from there supported his lifestyle.

In 1770, nearly half of Bengal was held under Bazee Zemin, with some districts recording 30,000 to 36,000 assignees and applications reaching 72,000 in one district. Similar revenue-free land grants were present across India, including the Madras Presidency, where by 1801, over 35% of cultivated land in the Ceded Districts was under such assignments. This was drastically reduced by British administrators to just 5%.

These assignments had historically supported education, religious institutions, and local governance. Reports from the Madras Presidency collectors indicate that revenue allowances had sustained Sanskrit and Persian learning, elementary education, and scholars. Some of these assignments were earlier appropriated by Tipu Sultan, but evidence suggests that under his rule, dispossession was largely symbolic or ineffective, and intended as a threat to opponents. However, when these areas came under formal British administration, dispossession became widespread and permanent.

The British dismantling of traditional revenue structures began in the mid-18th century and accelerated by 1770. Revenue formerly allocated for local social functions was redirected to the colonial state through:

Reclassification of Khalsa land: Most other categories were absorbed into taxable land under direct British control.

Drastic reductions in ‘district charges’: Local expenditures were slashed, with some districts (e.g., Trichnopoly) seeing a 93% cut.

Imposing higher tax rates: The British tax rate for cultivators under Bazee Zemin was now three or four times the original rate.

In the Madras Presidency survey, the Collector of Bellary, an extremely experienced bureaucrat, wrote a detailed explanation for what he perceived to be the cause of decline of Indian education:

Indian manufacturing suffered due to European imports.

Wealth was drained from India and concentrated in European hands. While Indian administrators spent the money on their own citizens, the Europeans were restricted by law to spend more money than allocated on India.

Revenue previously dedicated to learning was diverted, leading to the collapse of village schools (“in many villages where formerly there were school, there are now none”).

Under Hindu rule, education was supported by state patronage through grants. British rule, however, completely withdrew such support.

Thomas Munro the Governor of Madras Presidency, did admit that indigenous education “has no doubt been better in earlier times”, but even a powerful governor couldn’t state in formal records that this happened due to centralizing the revenue as the British did.

What we learn from this

This system of taxation that was followed prior to the British was ingenious in how it allotted taxes from different lands for different purposes. Tax rates were low, and a lot of the taxes were used for public works. Switching to an extractive tax system quite clearly impoverished the land and the people. But more than anything, it caused institutions to decline.

Prior colonizers destroyed universities, extracted wealth to pay tithe to the rulers in the Middle East or Central Asia, and stagnated science and technology, but due to the structure of how India was ruled, they didn’t have direct control over taxes. It was also possibly that they weren’t very educated that they didn’t know enough to interfere.

I’ll have to look this up, but I came across this in a podcast a while ago, take it as you will - India was administered by a bottom-up hierarchy, where the lowest was the village, and each level owed allegiance only to its next higher level. So this ensured that no matter who the ruler at the top was, it was business as usual in the villages, as the people lower in the hierarchy just pledged allegiance to whoever was at the top, and sent him taxes, while doing what they always had done. This made things quite resilient. Even if there was war and pillaging, people would just hide in neighboring villages or forests until the danger had passed and come back to pick up where they left off. So no matter what happened, children got educated, pursued a profession, and life went on.

It doesn’t seem like this system of taxation and paying for public goods exists as such anywhere in the world. I don’t know much about taxation, but I’d like someone who does to compare the old system with what we have today. Did it allow for less waste? Less misallocation? What happened if people were annoyed at how their taxes were spent?

Next week

Next week will be the final article based on this book. We will discuss the Colonial mentality which led to destroying this system. We will discuss what people like Marx and Macaulay said about the old education system, and why they wanted a new system. We will also look closer at the argument between Gandhi and British educationalist Philip Hartog on this issue and see how absurdly close to a present-day Twitter flame war it was.

Do you have any books you’d like me to read and discuss next? Please let me know either as an email reply or in the comments.

I want to keep this series free for all to read, but it takes me time and effort to bring these posts out, and it would be an incredible encouragement if you were to get a paid subscription.

Castes of Mind could be a good complimentary book to this one. I would suggest that one.